I went out with a girl once who told me she used to believe in Andrea Dworkin’s argument that all heterosexual sex is rape. Dworkin presented her radical feminist analysis in her 1987 book, Intercourse, which includes the line “violation is a synonym for intercourse” (154). On the same date, the girl asked me who’s a person I idolize, and I replied, without having to think, Kobe Bryant. Her immediate connotation of him, as could be seen through her scornful facial expression, was not of an incredibly successful basketball player, producer, writer, and family man, but of yet another man in a position of power who was accused of sexual assault and was never made to pay the price. Men get away with this shit all the time, she claimed as she attested his redemption, pretty confidently and absolutely, to his gender and social status. I didn’t attempt—nor believed I should—dispute her statement, though I believe there’s more to the story of how he un-villainized himself than that reductive argument. I became curious by how much more there is to that story, so decided to take a look at Kobe Bryant’s legacy, the one I unabashedly admire and felt my life has been shaped by and intwined into. That mandated a critical, at times even a scornful, look.

Early Days

He’s born in Philadelphia in 1978, the youngest of three, his dad an NBA player. At the age of six, his father moves to play in Italy, taking the family with him. He spends ages six-thirteen in Rieti and Reggio Calabria and Pistonia and Reggio Emilia, mastering Italian, isolation, and independence, all the while honing his own ball skills. His grandfather mails him cassettes of LA Lakers games for him to watch and watch and watch, and learn from. Talent alone will never suffice, he knows. He moves back to Philadelphia where he’s the first high school freshman to start for his school’s varsity team in decades, breaks Pennsylvania scoring records, and wins multiple national player of the year awards. He’s flashy and impressive. His coach praises him for his work ethic, despite him being the team’s most talented player. At a press conference in his high school gym, with the nation’s top college basketball programs vying for his signature, he famously says, “I have decided to skip college and take my talent to the NBA,” becoming the 6th player to ever do so.

I’m born in Ra’anana in 1994, the youngest of two, my dad a book translator. At the age of four, I join my local soccer club. I spend ages four-nineteen going through the ranks at the club, mastering camaraderie, commitment, and community, all the while honing my own ball skills. I look up YouTube highlight videos of Steven Gerrard—my favorite player—to watch and watch and watch, and learn from. Talent alone will never suffice, I hear. At no age am I my team’s most talented player—others are flashier and more impressive—but I am, throughout all ages, the team’s captain. I don’t break scoring records nor gain any national recognition, but I am constantly praised for my work ethic and commitment. As the time comes to transition into professional, senior clubs, no one vies for my signature, and, lying in bed, alone, late at night, I say to myself, “I need a fresh start.” I move to play college soccer for a small school in Florida.

***

The constant criticism throughout Kobe Bryant’s career was about his selfishness. It was his egocentric demeanor, people would claim, which broke up his dominant tandem with Shaquille O’Neal, forced the Lakers into giving him a massive contract in a salary capped league, and, most notably, never pass the damn ball. Those three prevented—respectively—him winning more titles, the Lakers rebuilding the team, and stars wanting to play alongside him.

It is that perceived selfishness, too, which left him, at the time of his retirement in 2016, as a 5 time NBA champion, the 3rd leading scorer in league history, NBA MVP, two-time NBA Finals MVP, 15 All-NBA Team accolade recipient, etc. etc. etc. You get the point. Seems like a pretty comforting return in exchange for being called selfish.

Besides, selfishness isn’t always a negative. In her magnificent article, What To Do With The Art Of Monstrous Men, Claire Dederer claims that amongst the many qualities one must possess to be a working artist, the first among equals, when it comes to necessary ingredients, is selfishness.

After Kobe’s death, in his memorial service, Shaq told a story about a time he went to confront Kobe after teammates were complaining he’s not passing the ball. There’s no I in team, O’Neal pleaded to Bryant, who responded, Yeah, but there’s an M-E in that motherfucker.

The Beginning

He is drafted by the Hornets and immediately traded to his favorite team, the Los Angeles Lakers. In his first three seasons, he wins the dunk contest, becomes the youngest All Star starter in league history, and shoots three consecutive airballs in the crunch time of a playoff game which his team ends up losing, terminating their season. [Bryant] was the only guy who had the guts at the time to take shots like that, Shaq said about the then 18-year-old phenom. Bryant would later say those high-pressure shots don’t phase him since he’d already put in the work and established his muscle memory.

In the three seasons that follow, Bryant and O’Neal (Or O’Neal and Bryant, depending on your allegiance) lead the Lakers to one of the most dominant runs in league history—a threepeat of championships, including an all-time best 15-1 record in the 2002 playoffs. Kobe is the youngest player in league history to earn three titles. Simultaneously, he begins accumulating individual accolades, and has his partner-in-crime proclaim him the best player in the game, before he reaches the age of 23.

I land in a country I don’t know to play for a team I’ve never heard of. When my new teammates meet me, they think I’m the new assistant coach, I’m later told. You’re 19? they perplex, given my beard and—apparently—mature features, we thought you were at least 33. It becomes a running joke that I’m the oldest NCAA athlete of all-time. Boarding planes for away trips, my teammates marvel at how well I was able to forge the birthdate on my passport.

In my first season, I spend extra hours in the gym and on the field, creating my own muscle memory, envisioning my college stint a mere pitstop on the road to achieving my dream of playing professional soccer. That year, in our conference playoffs, we’re upset by the bottom seed in the first round, but are encouraged by the undeniable, positive trajectory of our young team, comprising predominantly freshmen and sophomores.

***

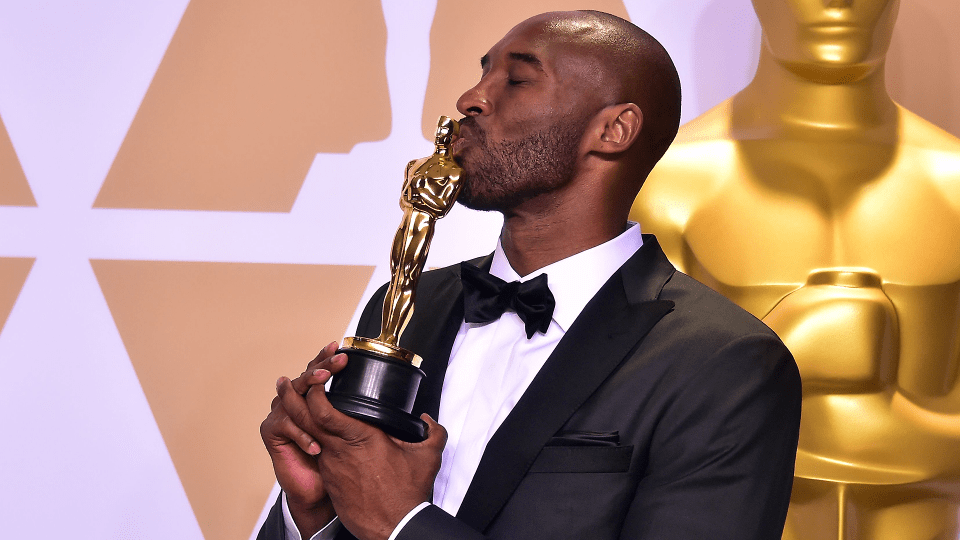

The self-righteous collaborative army likes to yell that since Bryant played a team sport, and was not an artist, he shouldn’t have been selfish. When asked what his response would be to people who call him selfish, Bryant famously said, Count to 5, alluding to the five team championships he’s won, well aware he’d have never achieved them on his own. Dederer’s quote about selfishness perhaps shouldn’t be attributed to Kobe, you could say, since he’s not an artist, but that’s debatable. After Kobe’s sudden death, eulogies from across the globe—near all of which I read and heard and basked in—came pouring in. Amongst them was one from national radio broadcaster, Colin Cowherd, who labeled Kobe as “The great artist. The canvas was empty, each possession he was a painter… So, it was not a coincidence when he left basketball, he won an Oscar in Hollywood.”

Of course he won an Oscar. Of course he published five New York Times Best Sellers. Of course he became a business mogul with a net worth of over 300 million dollars. His art, you see, was not the dribbling, producing, or writing. It was the process. In his jerseys’ retirement ceremony (the only player to ever have two numbers retired by the same team), Bryant said:

“Hopefully what you get from tonight is the understanding that, those times when you get up early and you work hard, those times when you stay up late and you work hard, those times when you don’t feel like working, you’re too tired, you don’t want to push yourself, but you do it anyway. That is actually the dream… If you guys can understand that, then what you’ll see happen is that you won’t accomplish your dreams. Your dreams won’t come true. Something greater will. And if you guys can understand that, then I’m doing my job as a father.”

That closing bit of his speech, you see, was addressed directly to Kobe’s three girls sitting in the front row (his wife, Vanessa, later birthed their fourth daughter). Elle Duncan, ESPN anchor, famously referred to Bryant as a “Girl Dad” in her eulogy of him, a title he self-proclaimed to when the two first met. This meeting took place two years before the helicopter crash that took Bryant’s and his second-eldest, Gianna’s, lives. It was an impromptu meeting in a hallway, initiated by Bryant noticing Duncan’s developing pregnant belly. Their conversation revolved around the joy of parenting daughters, and how Kobe would have “five more girls if he could.”

It didn’t matter to him to have a boy to continue his legacy on the court because A) He didn’t need a boy to do that. Gianna was a rising basketball star well-equipped to do so. B) He realized, as he neared the twilight of his career, that his legacy had nothing to do with basketball, but rather with the undeniable, relentless commitment to being great, in whatever field it may be. And sometimes, Bryant knew, that pursuit mandated a certain level of selfishness. And selfishness, as Dederer discusses it, is the artist’s necessity to block everything else out.

Turning Point

He’s gearing up for the 2003/04 season, riding high on confidence on the back of three titles. He flies out to Eagle, Colorado to undergo orthoscopic knee surgery. The media knows about some shoulder issue he’s dealing with during the offseason, but this cartilage injury is kept discrete. He and his team had done “a lot of research and found the [physicians in Eagle] are the best,” the transcript would later read. Around 2 AM of July 2nd, 2003, Bryant is confronted by two detectives at his hotel in Edwards, Colorado, in regards to a sexual assault accusation filed against him the evening prior. Throughout the two hour conversation between Bryant and the two officers, Bryant goes from denying having any sexual intercourse with the woman, to describing exactly how she bent over a chair, and how “she lifted up her skirt so [he] could, [he] could grab her butt.” Both acts Bryant had interpreted as her consent. No verbal consent is described in the exchange with the police. Bryant’s main concerns—as can be seen in the official, 57 page transcript released by Vail Daily in September of the following year—are his wife not finding out these sorts of allegation were made against him as she’ll be “infuriated,” and the story not going public.

He denies having raped the woman, but admits to infidelity. He says the only time she said “no” was when he asked if he could cum on her face. She got dressed and left soon after that “no,” and he finished himself off, he informs the detectives. The shirt he wore that night is taken as evidence, and is found through a DNA test to have three drops of the accuser’s blood on it. Further examination of the accuser finds evidence of vaginal trauma, which Bryant’s defense would later argue is consistent with having multiple sexual partners in two days, which she would later admit to. Kobe claims he has another mistress, who he asks they contact, as she’ll confirm him preferring to do it “from the back” and his tendency to grab his sexual partner’s neck. This mistress is more of a regular thing, which Vanessa, his wife, unsurprisingly, also doesn’t know about.

I’m made team captain ahead of my sophomore season, the team riding high on confidence after last year’s positive turnaround. We begin the season with two road victories against ranked opponents, shooting up our national rankings almost as high as our egos.

We win one more game for the remainder of the season, and despite the fact six out of seven teams in our conference qualify for the postseason, we miss the playoffs. I play on a sprained ankle all season, and when it’s over, scans reveal I have no cartilage left in my right ankle. I’m made an appointment for orthoscopic surgery after which I’ll be on crutches for six weeks. I vehemently refuse to be checked into a hotel post-op, arguing I’ll recover best where I feel at home—despite that being on a third floor apartment in a building with no elevator—but am forced to do so anyway. Friends take shifts monitoring me and my pillow-propped leg. My main concern is whether to have delivered hibachi or fried chicken for dinner.

***

Kobe’s always been my favorite. I didn’t watch any Laker games growing up, as the west coast tip-offs were customarily at 4 AM Israel time—long past my assigned bedtime and slightly before my wakeup time. Still, with little affliction to the game of basketball, affiliation to the city of Los Angeles, or admiration for either purple or gold, I loved Kobe. Part of it, I think, had to do with his name. Had he been as popular as he is/was had his name been Brad Bryant? Jared Bryant? You try shooting a paper ball into a trash can while yelling Vincent! and tell me if that feels right. So, I’d sit in front of the TV before school, long before smartphones and information were mere taps away, and wait for LA’s score to come scrolling through the screen. Kobe’s stat line didn’t dictate my entire daily mood, but I was—to an extent—emotionally invested in his number of points scored along with the W or L added to his team’s record, in that order of importance. I couldn’t tell you why, and at that young age, internal questions of why rarely surfaced. (External why?s, like most other kids, regularly featured.)

Having to select a wild animal to present a school science project on, I chose, obviously, a black mamba.

Decisions

He nicknames himself The Black Mamba. Nobody is allowed to give themselves a nickname, and it sticks, Colin Cowherd would say in his eulogy, Kobe did and it stuck. Force of nature. Kobe’s quoted saying he chose the nickname because of the snake’s ability to strike with 99% accuracy at maximum speed—a level of precision he aspires to have on the court. In reality, though, and as he himself discusses in his 2015 documentary, Muse, Kobe creates this venomous alter ego to separate his on- and off-the court personas.

The criminal case against him is dismissed after 14 months (due to the accuser’s refusal to testify), a civil case is settled outside of court, and he becomes a national villain. It’s Kobe that deals with lawyers, it’s The Black Mamba that laces the shoes. Endorsements such as Nike, Coca-Cola, and McDonald’s cut ties with him (some he would later regain). He’s boo’d in every arena he walks into, the team fails to win another ring, and his feud with Shaq becomes so toxic and public, till the organization has to pick between the pair, eventually trading O’Neal away. Bryant’s wife stays with him, but images of the couple at the press conference in which Bryant apologizes for what he did will, years later, become a classic meme. His embarrassed, apologetic ogle into the microphone, her eyes piercing him. Like a snake.

He embraces the Mamba Mentality, and in the three years after Shaq’s departure, goes on one of the best individual runs of all time. Like a true selfish artist, he blocks everything out. He earns scoring titles, is the youngest player to ever score ___ points; becomes the ____ highest scoring ____ since ____; has the most points scored over a ____ game span since ____. Fill in the blank as you please, it will probably hold true. The Lakers don’t make the playoffs in the first year, and are eliminated in the first round in the following two. Nearing the end of the 2006 season, Bryant’s second daughter, Gianna, is born. That same season, Shaq wins his first title post-Kobe, with the Miami Heat. Bryant’s generational on-court-talent shines as his selfish persona is solidified, and rumbles ensue about whether the Lakers picked the right star to carry them forward.

I go through my recovery process. Weeks of ankle mobility exercises, stem and ice treatments, and, by doctor’s orders, absolutely no weight applied on my right foot. No alcohol, either. I commit to the instructions for a while, but nearing the end of my six-week stint on crutches, host a party with my roommates. I’m propped on a stool, leg in a cast, immobile, being served cans of beer like I’m a Pharoah whose presence alone at this occasion mandates god-like service. People depart the party, I finally rise, wildly drunk, crutched, and stumble to bed. As I lay there, rumbles ensue in my stomach, and I walk—on two feet, uncrutched—to hurl into a toilet bowl. I wake up the next morning, ankle sorer than it’s been in weeks, sick not only from the alcohol, but also from the realization that I no longer have the ability or willingness to block everything—drinking, fun, friends—out, as is necessary to be a true artist. To have the Mamba Mentality.

***

In May of 2015, I flew to watch Steven Gerrard’s last home game for Liverpool. I played the position Gerrard played on the pitch, adorning the same number he did, adoring the football club he became a legend at. Every time I stepped onto the field, he was the person I tried to emulate. So, being able to be there for his final performance, saying goodbye to what had been such an influential figure in my life, while incredibly morose, is something I will cherish forever.

On April 13, 2016, my college roommates and I threw a watch party for the closing night of the NBA’s regular season. We set up two TV screens—one bigger than the other—so we could watch both of the iconic events which would end up transpiring that night: The Golden State Warriors earning their 73rd win of the season—an all-time record; Kobe Bryant playing the final game of his illustrious, twenty-year career. I sat on the couch, leg in a cast post-ankle surgery, and hopped with delirium as I watched—on the bigger screen, obviously—the self-proclaimed Black Mamba score 60 points with one last pull-up jumper, winning the game, and injecting venom into what was meant to be a Golden night.

That evening, though, was not morose, because it didn’t feel like goodbye. The influential figure Kobe has been in my life has nothing to do with his basketball skills. I never tried to emulate his jump shot, footwork, or dribbling skills. I was a fan of Kobe the basketball player, but the figure I admired was simply Kobe the person. So, when Kobe Bryant the player said goodbye, I wasn’t as sad, because the man I looked up to was still there. Basketball was simply the tool he used to show me, and the rest of the admiring world, the sacrifice required to achieve your dreams.

Career’s End

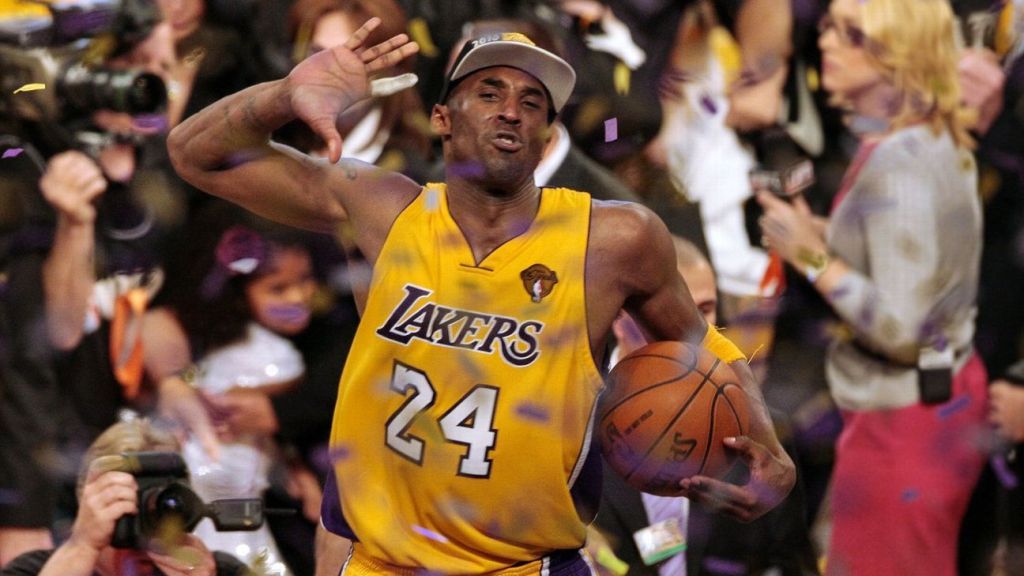

He continues to focus on one thing, and one thing only: basketball. He earns a reputation for playing through injury, wins his first MVP title in 2008, and carries the Lakers to their first Finals appearance post-Shaq, where they lose to the Boston Celtics. That summer, he wins his first Olympic gold medal, restoring USA Basketball’s glamour and stature after the team’s failure in 2004. The Beijing Olympic Games solidify him as a cultural icon, revered globally. In a star-studded USA team, he’s The Guy. The following season, he carries the Lakers to another Finals appearance, and is asked by a reporter why he isn’t smiling when holding a 2-0 series lead. His jaw clenched, his face stone-cold, he responds with, What’s there to be happy about? Job’s not finished. The response becomes a cult classic. The Lakers go on to win the series 4-1, with Kobe earning his first Finals MVP award. He leads the Lakers to the Finals the following year, where they meet the Celtics again—an opportunity to avenge the ’08 defeat. He plays with a cast on his broken finger and with a bone sprain on his ankle, requiring him to retreat to the locker room mid-games to have injected. As the final buzzer signals the Lakers Game 7 win, Bryant grabs the ball and lifts his casted finger to the roof, knowing he’s now situated atop the basketball, sports, and cultural world.

He’s lauded for his leadership and maturity, and is rewarded with his second NBA Finals MVP award. As the confetti descends onto the Staples Center floor in 2010, Kobe the father, the husband, stands at center court with his wife and two daughters, all of them holding up five fingers to the camera—signaling the number of rings now on the Black Mamba’s hand. In the press conference after the win, a reporter tells Bryant he knows what this title means for the team, but asks what it means to him, individually. With both of his daughters sitting on his lap, he answers, I just got one more than Shaq, and cracks a smile. You guys know how I am, he adds with a chuckle to a guffawing room, an aura of admirable arrogance around him, I don’t forget anything. His redemption story is complete.

I coast through the remainder of my college career. I’m lauded for my duality: for how serious and committed I am in season—I put in extra work, don’t touch alcohol even on free weekends—and how reckless and wild I am in the offseason. It’s like you’re two different people, people say. I embrace the duality. I win fitness tests, I pass out in bars; each, I consider, rendering the other all the more impressive. I come to terms with the fact I’m never going to be a professional soccer player. I’m dually good, singularly not great.

***

On January 26th, 2020, I was out grocery shopping. Sometimes, because I’m a better human than most, I leave my house without my phone. This was one of those occasions. I don’t usually document my supermarket trips, but when I returned home to a phone bombarded with texts, calls, and push notifications, the date, and where I was when the news about Kobe Bryant’s death broke, engraved themselves permanently into my memory.

I’m glad I didn’t have my phone when the word spread, since I had one more hour in a world that had Kobe Bryant, when most people were already trying to wrap their head around a world without him. It’s not like I was expecting to run into him in the aisles of an NYC C-Town, but it was nice not having to think about how, now, I will never run into him.

I stayed on Twitter for hours, soaking up words of pain, shock, and disbelief. Words of love, gratitude, and admiration. Everyone made their case for how the tragedy affected them. Friends and family reached out to me as if it was one of my loved ones who perished. They knew the impact Kobe had had on the way I view and value myself. Some people were closer to him than others, and for some the loss is vaster, but there’s no point in quantifying sorrow. One’s pain doesn’t come at the expense of another’s. We all hurt. We all lost someone. A father, a husband, a brother, a mentor, a friend, a role model, a favorite, an icon. As individual as a global loss can be. A pain so personal, shared so collectively.

It’s cliché to say I lost a part of myself when Kobe died, and I didn’t. I lost a part of me that I never had. I grew up idolizing a team and a sport, just like Kobe did. The difference was that he was able to make his dreams come true, whereas I failed. I failed because I couldn’t make the choice individuals have to make in order to be great. A choice to work hard, focus, dedicate, and sacrifice. I was inspired by those words which Kobe said in his documentary, but I was never able to do those things to the extent that he did. Few, if any, could. That’s why he had something I, and most, will never have. And that part of me, the one I never had, left with him that day.

Post-Athlete

He retires. There’s a notion that retirement becomes a pitfall for athletes, who, after decades of a narrow-visioned, single-minded commitment, are forced to relinquish the ground they’d been focusing on. Many find themselves in a different position in the sport—coaching, broadcasting. People posited that Kobe, who became a cultural synonym for dedication to a single endeavor, would positively struggle. But of course, he wins an Oscar for his animated short film, Dear Basketball.

He creates a series of young adult books he describes as “If Harry Potter and the Olympics had a baby,” revolving around self-acceptance. We all have fears, anxieties… We can’t ignore them, he tells Jimmy Fallon in an interview. He wants to teach young men, he says, that when things of that nature are ignored, they fester and take control over you. The fantasy series portrays how the characters use magic to face those fears which make them better athletes, and in turn, better people. One of the books in the series is made from green felt-like material, resembling a tennis ball, as the book revolves around a young tennis player who plays the sport to save her family’s life. Parts of the book can only be read in the dark, using a UV flashlight. It’s important for kids to have a sense of validation, he reasons the unusually high-end product he created, you pick this book up, and it feels like we matter, as children, we matter.

He opens The Mamba Sports Academy, a full-circle facility meant to help youth maximize their potential. He becomes one of the biggest proponents and advocates for women’s basketball. He’s a role model for all aspiring young players, and despite being a man, becomes an iconic figure amongst WNBA players (this isn’t to say he wasn’t such a figure for the NBA, which he undoubtedly was, too). He starts coaching Gianna’s team. As he had for Laker games his whole career, he helicopters to and from games and practices, usually with Gianna, and perhaps several other players/parents. She’s a beast, he says about his second-eldest, she’s way better than what I was at her age. Videos of father and daughter swarm the internet: sitting courtside at a game analyzing what’s transpiring in front of them; practicing jump shots at their home; her making a 360 layup in a game, the camera panning to him, awe-struck, admiring from the sideline.

He dies alongside his daughter and seven others in a helicopter crash just outside of Downtown LA. He died doing what he loves, Elle Duncan, holding back tears, says. Being a dad. Being a Girl Dad.

I finish my undergrad, then move to New York City to do my MFA in writing. I say goodbye to teammates who’ve become family, a locker room that’s become a home. I begin writing about myself and my team—not the one on the field, but the one in the locker room. I write essays about men; how they can be monstrous, wonderful. About how much I’ve learned from them, how much I still have to learn. How I admire them and am grateful for their existence in my life, how I am grateful to have left them behind me. I write about camaraderie and commitment and community, about the duality of being both a Dude and a Little Bitch. As I write an essay about the man I idolize, the most inspirational figure in my life, I try, like Kobe, to not forget anything.

***

Starting something, anything, is easy. How many kids pick up a basketball, how many novel outlines hide in drawers, how many diets don’t make it past day five? The finishing is the part that makes the artist, Dederer says in her article. The artist must be monster enough not just to start the work, but to complete it. And to commit all the little savageries that lie in between.

Kobe’s art is still revered long after his passing (perhaps more vigorously loved because of it). And his legacy, his Mamba Mentality, ironically, birthed not necessarily from his commitment of savageries like infidelity or alleged sexual abuse, but rather from his choice to move past them, and our choice to disregard them, accept his choice. His legend grew thanks to the decision of the two entities closest to him, his wife and his team, to stick by him despite it all.

In The Right To Sex, Amia Srinivasan’s magnificent and brilliant and depressing book, she writes about the alleged “conspiracy against men” people brought up in response to the MeToo movement. She ends her opening essay by disregarding any hope that “these disgraced but loved, ruined but rich, never to be employed again until they are employed again” men will ever change. “Why should they?” she asks, “Don’t you know who the fuck they are?”

Kobe’s scandal broke about fourteen years before the MeToo movement gained national attention. Many on the list of culprits never faced legal repercussions, but were socially marked, some publicly ostracized. Maybe today social media enables more immediate, ubiquitous PR retributions; maybe not enough time has passed for the public to conveniently forget and disregard the actions of Louis CK and Matt Lauer and the bunch. I can’t help but ask, though, whether if Kobe’s career had started fourteen year later than it did, with its first five years unfolding in the exact same way, would the eighteen years that followed have been feasible. I can’t help but ask whether this disgraced but loved, ruined but rich man did, in fact, change.

On the court, Kobe redeemed himself from being a selfish, immature, egotistical player by winning back-to-back titles for his team, his city. Basketball immortality for Kobe and the LA Lakers, announcer Mike Breen proclaimed at the time. Kobe’s off-the-court redemption seemed to go hand-in-hand with those titles, and was fully formed post-retirement, with his persona becoming that of a loving father and husband, a brilliant artist, and a kind-hearted, happy man. From ego-maniac to champion; alleged sexual assaulter to women’s icon.

We Meet

I stare at two screens, both approximately the size of basketball courts, which hang on the side of the parking lot across the street from Staples Center. They’re both circulating the same three Nike ads. One of the ads features Sabrina Ionescu—no. 1 pick in the 2019 WNBA draft—making a layup and celebrating an NCAA title, with the caption “Do it to begin a legacy.” The caption evaporates, then replaced with “Do it to continue a legacy,” over three black and white images of Ionescu with her long time role-model and icon, Kobe Bryant, and his daughter, Gianna.

I’m sitting on the other side of the road, at the feet of the arena, where there’s a small gathering of around 100 people. For peak-pandemic days in Los Angeles, it feels crowded. People await their turn to take a picture next to a shrine—a collection of cardboard cutouts of Bryant’s face, his jerseys, stills of his iconic moments, bouquets of flowers, candles. In the last couple of months, driving across the US, I’ve seen this image often. People posing next to The Thing—the view from Angel’s Landing, the Beale Street sign, the Grassy Knolls—presumably so they could show the photo to people, or their future-self, and be able to say I was at this special place.

But there’s an added uniqueness to the people around me, as today is January 26th, 2021, marking the one year anniversary of Kobe’s death. I was at this special place at this special time, they’ll be able to say. I don’t pose by the shrine (nor did I pose at Angel’s Landing, Beale St., etc.) because a part of me detests the act. I want to believe I’m here because I want to be here, not because I want to be able to tell people I was here. (I recognize the irony of me, now, telling you I was there.)

There are vendors selling merchandise—scarves, shirts—along the road, turning grief into a commodity. Some are selling purple and gold beads, reminding me of Mardi Gras. The beads flash under the California sun and are available for a price, rather than as a reward, as they do in New Orleans, for flashing under the sun. There’s a middle aged man wearing Kobe’s purple rookie jersey; a young girl, probably barely born when Kobe retired, wearing Gianna’s no. 2 jersey; a college aged guy, as if plucked straight from a frat party, wearing a gold Bryant top over a black hoodie. On a balustrade to my left, a father and young girl sit, necks bent backwards, watching the Nike ads across the street.

One of Kobe’s famous quotes is, Heroes come and go, but legends never die. Legends live as long as the story does, and Kobe’s story is still very much alive. Three little girls, probably aged two, four, and six, probably cousins or sisters or friends, hop and giggle behind me. Their father somewhere around, surely, commemorating this moment for himself. Perhaps the father, like me, wants to live his life like Kobe did; wants to engrain his girls with an appreciation for dedication, tenacity, and the process. The girls, perhaps unaware yet, are a part of the legend now, too.

I sit, jot down notes in my yellow pad, knowing there’ll come a day where I, for myself, will have to look at Kobe’s legend not through admiring eyes, but critical ones.

***

I do believe that timing played a significant role. Particularly nowadays, and particularly in an NBA with a progressive commissioner like Adam Silver, who gave full support for players’ fight for racial justice in the form of cancelling games as protest, using courts and jerseys as platforms for anti-racism messages, who has built a reputation for punishing behavior detrimental to the public image of the league, Kobe’s scandal wouldn’t have gone down as smoothly as it did in 2003. Public pressure and social media would’ve put an onus on the Lakers to handle things in a manner that doesn’t condone Kobe’s behavior, which may have disabled Bryant from playing in games for the 14 months the court case was still open (he occasionally flew on a private jet directly from games back to the airport in Eagle, which stands a few blocks away from the courthouse).

His gender and the social climate of the time were passive cleansing contributors, but looking at what he did from 2004 onwards, it seems he actively sought out redemption. In an interview with the LA Times after the civil case was settled, he told J.A. Adande, It’s important that the image that’s out there is the real image of who I am as a person. That image has come to be that of a man who started a foundation meant “To provide funding for programs that offer equal opportunities for young women in sports;” a man who WNBA Commissioner, Cathy Englebert said was admired “not just as a legendary basketball player, but as a father, a youth coach and a role model for future generations of athletes.” He did so by investing his money into the elevation of women’s sports, and using his platform to promote awareness for the women’s game.

When I made that exact point to a friend, she said there could be something questionable about this sort of philanthropy, too. Something about the man’s usage of his resources to groom and situate himself as a provider for weaker, younger women. She made a claim about the dynamic of power established between him and the young women he’d allegedly helped. Quite a cynical take, in my mind, which my gut reaction to was extreme defensiveness. I wanted to stamp her statement absurd, make the case for Kobe Bryant being a genuinely good man, and argue that questioning the validity of his intentions could, to some men, be discouraging of engaging with the other side at all. Her claim—which, to be fair, she proposed rather than propagated—pissed me off; I’d have preferred her attacking my name rather than his. I didn’t argue back, though, as I felt there was more for me to gain from being contemplative than from being defensive. It’s important, when arguing, to consider whether you’re trying to make a point to the other side, or to yourself.

The biggest problem with my friend’s suggestion is that there is room to make it. That her argument is—as much as I dislike saying it—valid. A dog that barks doesn’t bite, but will a dog that bit ever bite again?

The events which transpired on the night of July 2nd, 2003 affected first and foremost the accuser and her family, then Vanessa Bryant and her family. They affected the LA Lakers and the NBA and endorsements and, amongst all those, the events tainted Kobe’s legacy forever. But Kobe was permitted to rectify himself, and he spent the rest of his life painting his canvas so gloriously that most forgot that stain is even there. Ostracizing Kobe for good at the age of 24 would’ve prevented heaps of publicity and dollars going towards the advancement of equality in sports, as well as countless words, actions, and moments which inspired a generation.

Perhaps Kobe was given another chance because of his gender, perhaps because of his talent, perhaps because of his social status, or perhaps because enough time had passed from the accusation against him. Perhaps, though, he was able to do as good a job as any cleaning his slate and becoming ubiquitously admired because the extent of the stain on his legacy—ranging somewhere between infidelity and rape—we never learned the exact size of. Perhaps it’s our fault for not trying hard enough to learn.

When we look back at his impressive, generational, uncanny legacy, now, it’s important that we choose to not only see the stain, but to talk about it. It’s important, to me, that I do so.

Now

I sit down to write an essay about Kobe Bryant. I’ve always felt my life was intertwined with his. Or, rather, mine was intertwined into his. I had dreams of being an athletic icon playing for my favorite team, have dreams of winning Oscars, publishing NYT Best Sellers; all of which Kobe accomplished. The lines between aspirations I’ve always had and ones that took shape because Kobe accomplished them first are blurred by this point. As I retell his story in this essay, I try to mimic how his one major blemish took form, and was then moved past, rarely resurfaced. I try to intertwine our stories, find the spots where we both found ourselves at similar forks in the road, and show how we went down different tines. How his ability to block out all which didn’t directly aid his cause allowed him to achieve his dreams, and prevented me from reaching mine.

More than anything, I want to convey how I’ve always been enamored with Kobe’s words, not his actions. They always felt more relatable, attainable. I could never score 81 points in an NBA game, but I can wake up early, stay up late, and work hard even when I don’t feel like working. I have a quote from Kobe hung up in my room, which he said in an interview before his final game:

If I had the power to turn back time, I would never use it… Because then every moment that you go through means absolutely nothing… So, it loses its flavor, it loses its beauty, and things are final, and you know the moments won’t ever come again.

I referenced that quote in the goodbye I penned to him the day he died, and added how his life was beautiful, full of flavor, and now, it is final. How I will do my best to live every moment that I can. How I know he said he would never, but I wish I could turn back time just once. Once. Just so I could meet him and tell him that without ever meeting me, he changed my life, and for that, I am eternally grateful.

As I trudge through my essay, I read the 57 page police report and think back to Kobe’s quote. It’s mind boggling to me, initially, that the same man whose words I’ve basked in for 26 years, who always seemed so composed and articulate and eloquent, is on record sounding so guilty, flawed, and monstrous. But of course he is. We all are

***

There was a version of this essay, in my mind, in which I tell you I was accused of sexual assault. Maybe even one in which the Andrea Dworkin fan from the beginning accuses me of rape despite the fact we merely engaged in consensual, heterosexual intercourse. But there’s no big revelation at the end here, one in which I admit to committing a heinous act of that sort, and how that’s the final knot bonding mine and Kobe’s life; how that’s the reason I spent so much time contemplating his road to redemption. I’m relieved (and feel the need) to say I’ve never done something like that, nor been accused of something like that.

There is, though, a certain parallel to be drawn between Dworkin’s theory about heterosexual intercourse and Kobe’s story. This parallel, I think, can serve as a springboard for a discussion about the definitions of consent, assault, and violation. While the narrative of obtaining verbal consent, aligning expectations, and ensuring levels of comfort is an important one to propagate, that’s not what I’m here to do in this essay.

I’m here to ask myself in what manner do we accept the monstrosities attributed to us? This, in-turn, begs the question of who “Us” is. In this essay, the “Us” is me and Kobe, but he’s far from the only example of an athlete finding himself in that position.

Over the last couple of weeks (end of 2020/21 NBA season), two controversial hires were made in the NBA, both in the ballpark of this essay. First, Chauncey Billups, aka Mr. Big Shot, who is basketball-universally revered, was hired as the Portland Trail Blazers new head coach. Billups had a rape allegation thrusted against him in 1997, though he was never convicted, and a civil case was settled with the accuser. Slight controversy ensued when Portland’s star, Damian Lillard, vaguely dismissed/didn’t respond “strongly enough” when he learned about Billups’s past. Second, Jason Kidd, basketball hall of famer, was hired as head coach by the Dallas Mavericks. Kidd was arrested for domestic abuse in 2001, and has multiple such incidents on his track record. The Mavericks, by the way, were at the center of sexual assault and misconduct allegations within the business’s front office in 2018, so have a dodgy record prior to this hire. Both guys were hired, and will be assessed from here on out based on their W-L columns, with their dicey past dusted under the carpet, or, I should say, swept under the court, never to resurface.

There are plenty more. There’s the Derek Fisher and Matt Barnes scandal as another NBA example, Kareem Hunt or Ray Rice or Ben Roethlisberger from the NFL, Neymar, Mike Tyson, Conor McGregor. The list goes on and on and on, at some point crossing the threshold of depressing and infuriating, and reaching the dangerous isle of numbness. Perhaps it is that numbness, ambivalence, and disregard which, deep down, I want to try and fight.

The reason I made this essay’s “Us” me and Kobe is, first and foremost, my personal adoration of him. Secondly, because of how enigmatically captivating I find him to be, and how he’s far removed from me not only in career paths, but in age. Maybe it’d have made more sense to make this essay’s “Us” myself and a different athlete who’s had sexual assault allegations made against him. An assaulter who, we all agree, never suffered from adequate repercussions, and who was closer in age to me, with a college career spanning the same years mine did. An athlete with an abysmal story which lacks any nuance, and who—legal retributions or lack thereof aside—is colloquially detested. An athlete who’s not made his way back into the center of the frame, though despite how unequivocally monstrous his character is perceived to be, it’s hard to rule out him being awarded a second chance. But while it would have made more sense, the choice in this essay was mine, and in no world would I ever choose to place myself in an “Us” with Brock Turner.

Then again, it’s not always my choice.

I say I’ve mastered camaraderie, commitment, and community, and I’d like to think that I have, on the field. But there are many other “Us-es” I belong to—young men, jocks, Kobe fans, straight males, human beings—whose affiliations I have not mastered, despite my hope to do so. It seems impossible, unattainable even, to fully comprehend the mechanisms of these social groups, but like a wise man once said, It’s not about the destination, it’s about the process. And my process started by questioning the validity and complexity of Kobe Bryant’s legacy.

There is no final landing tarmac here where I tell you I’ve decided to stop canonizing Kobe Bryant’s words because eighteen years ago he was accused of sexually assaulting a woman, nor one where I choose to disregard completely what happened on July 2nd, 2003 because it makes me uncomfortable. All I have to show for, truly, is an active decision to look at the 1% of Kobe Bryant’s life I can’t blindly and devoutly adore.

I’m here to ask myself if I’ve ever seen a friend walk out of a party with a girl who didn’t seem fully coherent. If I’ve ever been told a male escapade intended to be self-glorifying but coming across as questionable, at best. If, while writing this, I thought back to actions I’ve taken or words I’ve said, which, when situated next to what people will one day eulogize me for, will be seen as jarring and mind-boggling. I’m here to ask myself if when any of these moments happened, I chose to look away, disregard, erase. I know the answer is yes; I know I have. I’m here, lastly, to wonder whether you, whoever you are, would be willing to ask yourself the same questions.

I don’t intend on this essay being a thunderous “call-to-arms,” but rather more of a slight nudge, and a, Hey, have you ever looked at this?

There are flaws in suggesting men shouldn’t be monsters because of the negative affect the monstrosity will have on their own image. I’d like to urge guys to be well-intentioned and encourage them to act from a place of genuine kindness and consideration of the other, but arguing for that and that alone is, unfortunately, slightly naive. We’re all selfish, on some level, and sometimes it is that selfishness that can lead us to be better people.

I’d be cynical, too, to suggest this essay should serve as a reminder for what’s at stake for us, men, whenever we do anything. At the same time, I’d be hypocritical if didn’t say exactly that. It’d be hypocritical of me if I didn’t say that I believe that an argument which stems from a selfish mindset can work. I’d be remiss, too, if I didn’t also advocate for male accountability, self-interrogation, and cultural examination. My convoluted argument is, I guess, an amalgamation of selfishness and altruism, kindness and egotism. A duality, per se.

Even those of us who aren’t monsters commit monstrosities—of various sizes—from time to time, much like those of us who aren’t artists sometimes create art. It’s easy to point at a monster and say they’re a monster, but an effortless path leads to a futile destination.

The challenge, and what makes the artist, is the finishing, but the road is where we find our art. And art doesn’t have to be a painting, an essay, or even a jump shot. Sometimes, art can be as simple as choosing to remember, attempting to reconcile with that which would be so much easier to forget.

Leave a comment